The True Story of 'The Miracle Pilot' and His 120 MPH Water Landing

“Hearst Magazines and Verizon Media may earn commission or revenue on some items through the links below.”

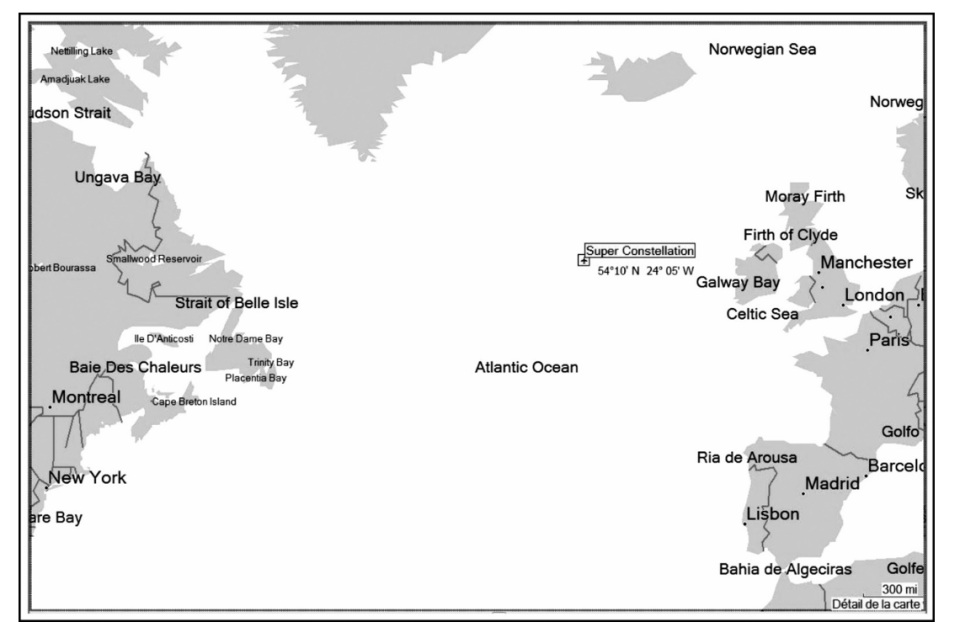

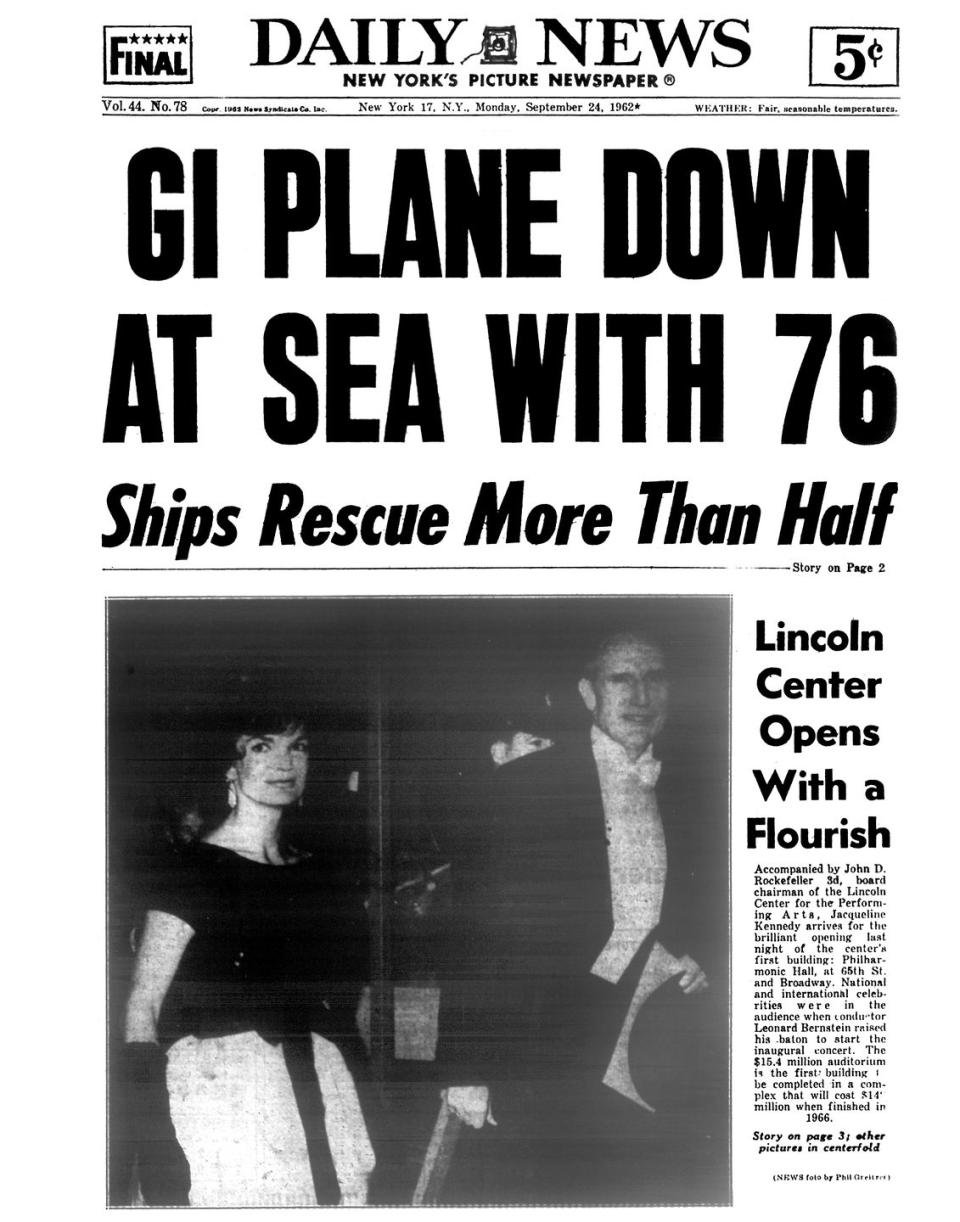

Eric Lindner's Tiger in the Sea: The Ditching of Flying Tiger 923 and the Desperate Struggle for Survival tells the story of pilot John Murray's 1962 life-saving "ditch" of an L-1049H Super Constellation in the North Atlantic ocean, a barely controlled water landing with 76 passengers and crew members onboard. The effort captivated the world at the height of the Cold War. Newspapers from London to Los Angeles ran breaking updates of the crash's aftermath, and President Kennedy received hourly updates concerning the fates of all involved.

Lindner conducted dozens of interviews with survivors and eyewitnesses to write Tiger in the Sea. His account is definitive, unearthing details and insights from Murray and others that reveal the full extent of the event's unprecedented danger, as well as Murray and his crew's miraculous airmanship and extraordinary ingenuity.

Here, read an exclusive excerpt from Tiger in the Sea.

As Flying Tiger 923 sliced through the dark sky over the Atlantic, a thousand miles from land on the way to Frankfurt from Newfoundland, a red flash on the instrument panel caught Captain John Murray’s eye: Fire in engine no. 3; inboard, right side. The 73-ton Lockheed 1049H Super Constellation had 76 people onboard, but the 44-year-old pilot from Oyster Bay, Long Island, wasn’t rattled. He’d survived back-to-back plane crashes as a flight instructor in Detroit, Egyptian anti-aircraft as a black ops freelancer, and several overwater engine failures as a commercial pilot. Murray knew the most likely explanation for the signal was a transient electrical malfunction—the aircraft’s fire detection system was notoriously finicky—but still, Murray was puzzled: There was no alarm bell to go along with the flash. His log books accounted for 20 years of fire warnings, but zero entries spoke of a transient flash without an accompanying alarm.

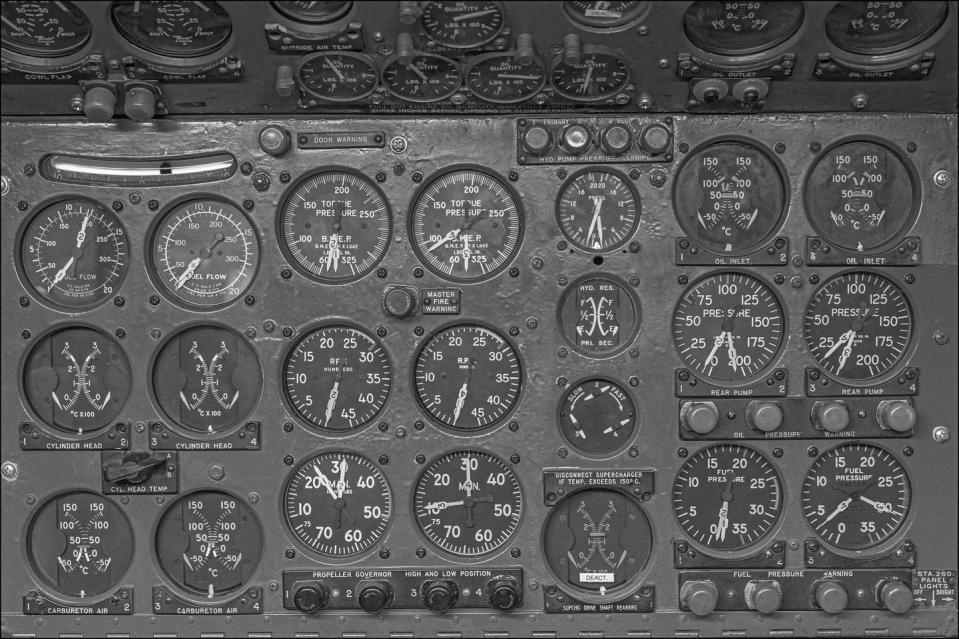

Murray sat in the left cockpit seat, beside first officer Bob Parker. Navigator Sam “Hard Luck” Nicholson and flight engineer Jim Garrett sat behind them. The flight deck was a claustrophobic clutter of manuals, personal belongings, floor-to-ceiling electronics, and cigarette smoke. To eliminate the potential for lethal drag, Murray instructed Garrett to feather engine no. 3, then stand by to discharge fire suppressant.

Garrett pulled the throttle back to idle and feathered the engine’s propellor blades so they were parallel to the slipstream, then he cut off the fuel-air mixture control to disable the troubled engine. A bell clanged, and slumbering passengers jolted awake—it was a fire. Outside, crewmembers and passengers could see the flaming engine oil and white hot steel fragments shooting from the no. 3 engine’s exhaust stacks. The pyrotechnics lit up the sky.

Garrett raised his voice above the alarm bell: “Ready to discharge, Captain.”

“Fire one bottle,” Murray said.

“Copy that.” Garrett lifted the small red spring-loaded aluminum cover labeled eng. fire dhg., moved the switch to the discharge position, and shot an extinguishing agent into the no. 3 engine. The alarm stopped. The fire light on the control panel went dark.

• • •

According to Aviation Safety Network statistics, which standardize accidents by passenger miles flown, when Flying Tiger 923 took off on September 23, 1962, air travel was 100 times more dangerous than it is today. As for the Constellation (“Connie”) series, nearly one of every five built between 1950 and 1958 had crashed or was otherwise out of commission. In March 1962, two Connies met ill-fated ends within hours of one another: one crashed in Alaska; the other disappeared somewhere over the Pacific.

Murray’s Connie had rolled off a Burbank assembly line on February 20, 1958, but Howard Hughes had conceived the plane all the way back in 1937. Because Connie used the same basic piston technology that powered wagons in 1844 (as opposed to the jet turbine first used in 1939), and because its Wright reciprocating engine wasn’t as reliable as its chief competitor’s Pratt & Whitney, Lockheed stopped producing Constellations a few months after Murray’s plane was manufactured. Yet Murray himself still found a lot to like in his plane. He liked her range, ruggedness, and versatility, as well as her unique triple tail fins. He’d flown her 4,300 hours, often in dire conditions. She’d never let him down.

• • •

The crisis seemed over by 8:11 p.m, three hours after takeoff. The fire was out, and any damage seemed contained within the exhaust stacks. Murray decided against shooting a second bottle of suppressant.

But flight engineer Garrett, a recent hire, had forgotten to close the no. 3 engine firewall. Moments after he closed the no. 1 firewall—on the left outboard engine—by mistake, his colleagues heard what they described as “a shrill obscene snarl” from the left side of the aircraft. “Runaway on number one!” Parker yelled.

The error had triggered a chain reaction: When the left outboard’s hydraulic subsystem stopped pumping, blast air stopped cooling the generator, and fuel and oil stopped flowing to the motor and governor. This caused the propellor to spin out of control at close to the speed of sound. If the 13-foot blades were to break free, the projectiles could down the plane.

Murray muscled all the throttles back and decelerated Connie to 210 mph. Then he began easing her nose up, leveraging the air current into a makeshift brake. The blades slowed enough to allow Garrett to feather the no. 1. Disaster was averted again.

But the plane had lost two of its four engines in seven minutes. Connie was 972 miles from land, hundreds from the nearest ship. Murray knew he shouldn’t try to make it all the way to Frankfurt, so he laid out three alternatives: pull up short at Shannon Airport, about 1,000 miles closer; divert north to Keflavik Airport, closer still; or, the worst case scenario, attempt a ditching, what the FAA referred to as a “controlled water landing.” Parker worked the radio, trying to keep the main rescue control center in Cornwall apprised of Flying Tiger 923’s coordinates and altitude, but he was struggling to communicate over the narrow, mid-oceanic high-frequency band. Garrett checked the performance charts to determine the cruising altitude that would cause the least strain per the current engine configuration and weight: 5,000 feet. They had enough fuel to reach Ireland.

But at 9:12 p.m. another red light flashed in the cockpit: fire in engine no. 2. Murray reduced power, Garrett feathered no. 2, the light went out, and the nerve-fraying alarm fell silent, but now the plane was flying on one engine. It couldn’t do so for long, so Garrett reversed the feather on no. 2. The props realigned, and Flying Tiger 923 was back to two engines; thankfully, one on each wing.

After Hard Luck plotted a course for Ireland, Murray led a discussion on whether to deviate so as to overfly Britain’s Ocean Station Juliett or America’s Ocean Station Charlie. If ditching proved necessary it would be much better to do so near one of the floating, well-provisioned outposts rather than in the middle of the open, frigid sea.

Deviating wasn’t a straightforward proposition, however. First, while the British weather station was 100 miles closer (250 miles away versus 350 miles for the American station), the U.S. Coast Guard cutter Owasco was moored beside Charlie; it could travel to the crash site faster than either outpost in the event people needed rescue. Second, overflying either station could add another 175 miles of engine strain. Murray directed Parker to establish contact with the Owasco, then asked the chief stewardess to lead her three colleagues in a ditching drill. Passengers handed over their pens, pocketknives, reading glasses, dentures, belts, and anything else that might injure them on impact, or puncture their life jackets or rafts.

The flight deck was hot, humid, and hectic. As the plane descended and settled into a cruising speed of 168 mph, the uneven thrust from the full-powered right outboard and hobbled left inboard, coupled with the tacky altimeter and jumpy rpm, told Murray he wasn’t out of the woods. The pilot considered dumping fuel to trim the plane’s weight—the excess fuel beyond what they needed to reach Shannon was 5 percent of the load—but the added buoyancy of an empty tank wasn’t worth losing the cushion. He kept the fuel.

Yet another bell rang at 9:27 p.m. A metallic grinding and screeching could be heard from the left side of the plane. Out the windows, a shower of sparks lit up the moonless sky. It seemed the no. 2 engine might explode any second.

Murray throttled back on no. 2. The plane slowed, its nose lifted, the bell stopped ringing, and the fire light went out. But the pilot knew if he kept throttling back he’d never reach Ireland. He’d exhausted all his options.

• • •

Circa 1962, the U.S. Coast Guard defined a “successful ditching” to mean (i) the aircraft didn’t sink immediately, (ii) it remained mostly intact, and (iii) a majority onboard survived impact. No pilot had ever successfully ditched in such brutal conditions: a pitch-black night, winds gusting to 65 mph, 20-foot seas. The North Atlantic seabed was a mausoleum for the remains of countless planes and ships, including the Titanic and dozens of Spanish galleons. For those aboard, hitting the water would feel like crashing onto a cement runway. Murray, a husband and father of five, knew his aluminum plane would most likely break apart on impact or sink in seconds. Land was 650 miles away.

At 9:42, another alarm bell rang out. The left inboard engine began shooting fiery blue-black carbonized fuel globules the size of a fist past the windows. Murray silenced the alarm but told his crew: “Ditching seems probable now.”

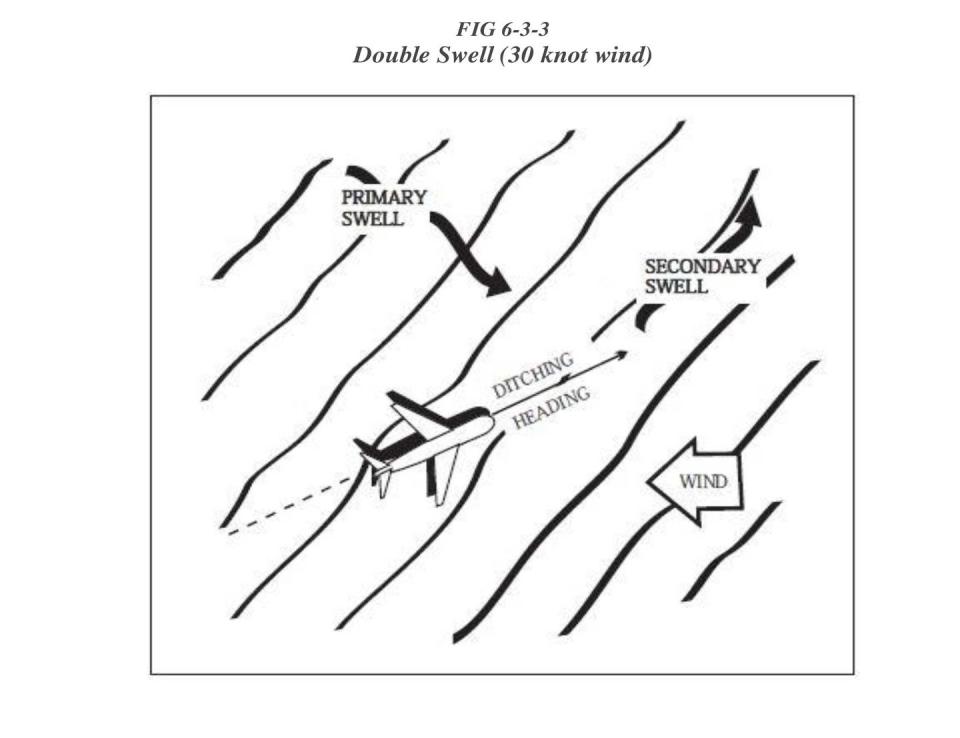

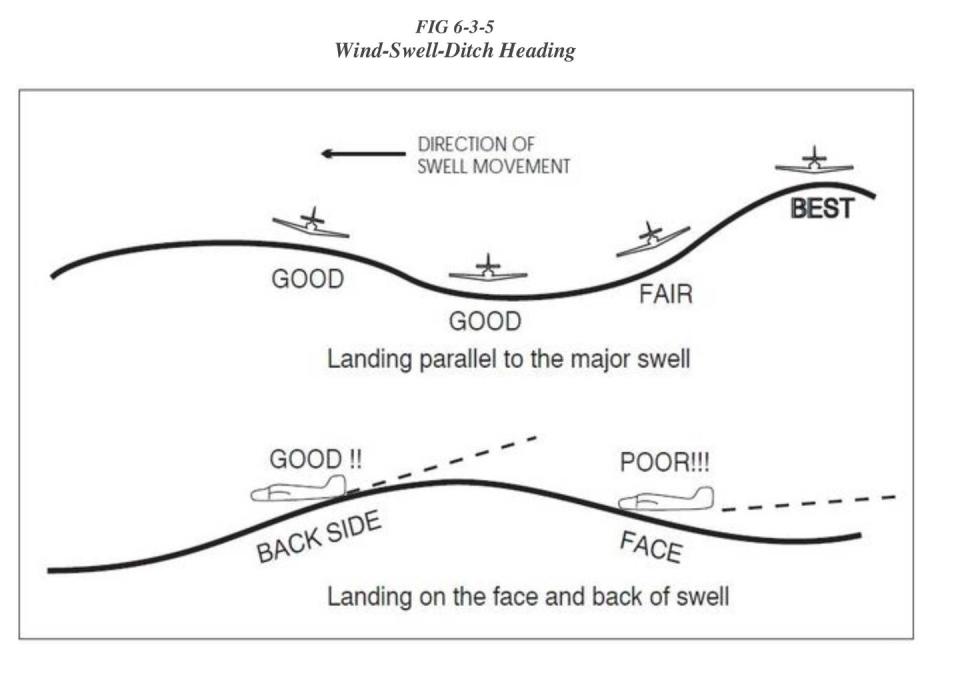

Absent a significant change in the swells’ direction, velocity, or height, Murray said he intended to fly into the wind, toward the swells, and touch down between two of them. His colleagues were perplexed. The manual read: “Never land into the face of a swell or within 45 degrees of it.” These same instructions were also in all the Navy tip sheets, Flight Safety Foundation bulletins, Air Line Pilots Association newsletters, and Civil Aeronautics Board accident reports. Murray explained: “In almost every ditching training session, after a discussion of why it’s better to land parallel to the swells, there’d always be an old-time flying boat captain who landed his Sikorsky or Boeing into the swells.” The Coast Guard’s instructions were “sensible in theory,” he added, but they didn’t apply to Connie’s unprecedented situation. Because Murray felt the stiff winds at sea level would cut his speed and minimize sideways drift, the Flying Tiger captain said he intended to ditch like the flying boat captains.

Where to touch down was the next question, but a “height perception illusion,” unique to ditching, hindered Murray’s vision. For the human eye to process inputs, it needs a canvas of crisp, discrete focal points on which to paint a comprehensible picture. Seldom is this a problem when landing at an airport, since the trees, telephone poles, and air traffic control towers create a concrete referential pointillism easily processed by the eye. But during a ditching over active water, the sky merges into the sea, bleeds into the horizon, and plays tricks on a pilot’s eyes, wreaking havoc with their depth perception. Illusions lead pilots to hit the water at the wrong spot or angle; too soon or too late; too slow or too fast.

As he dipped Connie below 2,000 feet, Murray could discern the direction of the swells. He estimated their height to be between 15 and 20 feet, the interval separating them 150 to 175 feet. Were he to hit a swell, it would act as a ferocious impact force-multiplier against the aircraft. At best, he had 12 feet of wiggle room to lay down the 163-foot plane. With winds buffeting Connie 15 to 25 feet in every direction, and the possibility of hidden secondary swells beneath the whitecaps below, he’d have to perfectly calibrate the point and manner of impact.

Then, it started to rain like mad. But as the moon emerged from hiding and lightened the sky, Murray’s height-perception illusion dissipated and he could more clearly make out the distance between swells: about 200 feet, crest to crest. That gave him a 37-foot margin of error—for a plane traveling 176 feet per second. The waves were high and powerful enough to snap Connie’s wings off and send the four life rafts tucked in their bays to the bottom of the sea.

The optimal descent slope was 25 feet per second, but Flying Tiger 923 was heading towards the sea at 34 fps. Murray fought to flatten the grade, but gravity was tugging Connie toward the ocean. If he didn’t elevate fast, they’d hit the water at a catastrophic angle and velocity.

He wrestled against the opposing winds, struggling to maintain an even keel. Were either wing to clip one of the powerful swells, Connie would flip into a horrifying cartwheel, breaking apart, sinking, and likely killing everyone. The lone working engine—the right outboard, no. 4—billowed angry blue flames as it tried to do the work of four. No. 2’s unfeathered prop rotated erratically at the mercy of the wind. As the landing lights illuminated his point of impact, Murray called out over the 121.5 frequency: “Mayday. About to ditch. Position at 2212 Zulu Fifty-Four North, Twenty-Four West. One engine serviceable. Souls on board seventy-six. Request shipping in area prepare to search. Over.”

The plane hit the water at 120 miles per hour—560 miles from land.

• • •

All 76 passengers and crew members survived the impact and evacuated the wreck. However, after seven nightmarish hours in the rough, bitterly cold North Atlantic, only 48 survivors boarded the first ship on the scene, a Swiss grain freighter. The remaining 28 died from drowning: many during a frantic, futile search to find the four missing life rafts.

Flying Tiger 923’s sea crash was the world’s top story for a week. In the U.S., news bulletins interrupted the massively popular Bonanza to give updates on the crash, rescuers appeared on The Ed Sullivan Show before an at-home audience of 40 million viewers, and in terms of column inches, the story received more newspaper coverage than astronaut John Glenn’s Florida splash-down earlier that year. Anchors and aviators alike hailed “the miracle pilot,” but how was John Murray able to overcome so many mechanical problems, manage so many simultaneous crises, and do what most experts said was impossible?

First, 85 percent of Murray’s piloting since 1957 came at the helm of a Super Constellation, but he also effected water landings on seaplanes and amphibians (he held ratings in both). Second, his engineering training primed his decision-making to be anchored in physics, not convention. Third, he was a precise delegator and leader, with a clarity of purpose and serenity fostered by a deep personal faith. He didn’t make reactive, survival-motivated decisions, but decisions based on a personal sense of responsibility for the 75 other lives onboard. A pilot colleague once said about him, “John knew he was expendable. It was the definition of what being a captain is all about: going down with your ship.”

Adapted from Tiger in the Sea: The Ditching of Flying Tiger 923 and the Desperate Struggle for Survival (Lyons Press; May 14, 2021). You can connect with the author, Eric Lindner, on LinkedIn.

You Might Also Like